Defenses to Negligence: Key Strategies for Texas Personal Injury

Discover defenses to negligence claims in Texas and how fault rules, assumption of risk, and other strategies can affect your case.

When an accident happens, it's natural to think the person at fault is automatically 100% responsible. But the legal system isn't quite so simple. A defendant can raise several defenses to negligence that can dramatically shift the outcome, either by reducing their share of the blame or eliminating it entirely.

These defenses aren't just technicalities; they’re designed to make sure the final result is fair by bringing all the relevant facts to light.

How a Defense Can Reshape a Negligence Claim

Imagine a personal injury claim is a story. The injured person (the plaintiff) tells their version, explaining how the other party’s (the defendant's) carelessness led to their injuries. A negligence defense is the defendant’s chance to add a critical piece to that story—a piece that could completely change how it ends.

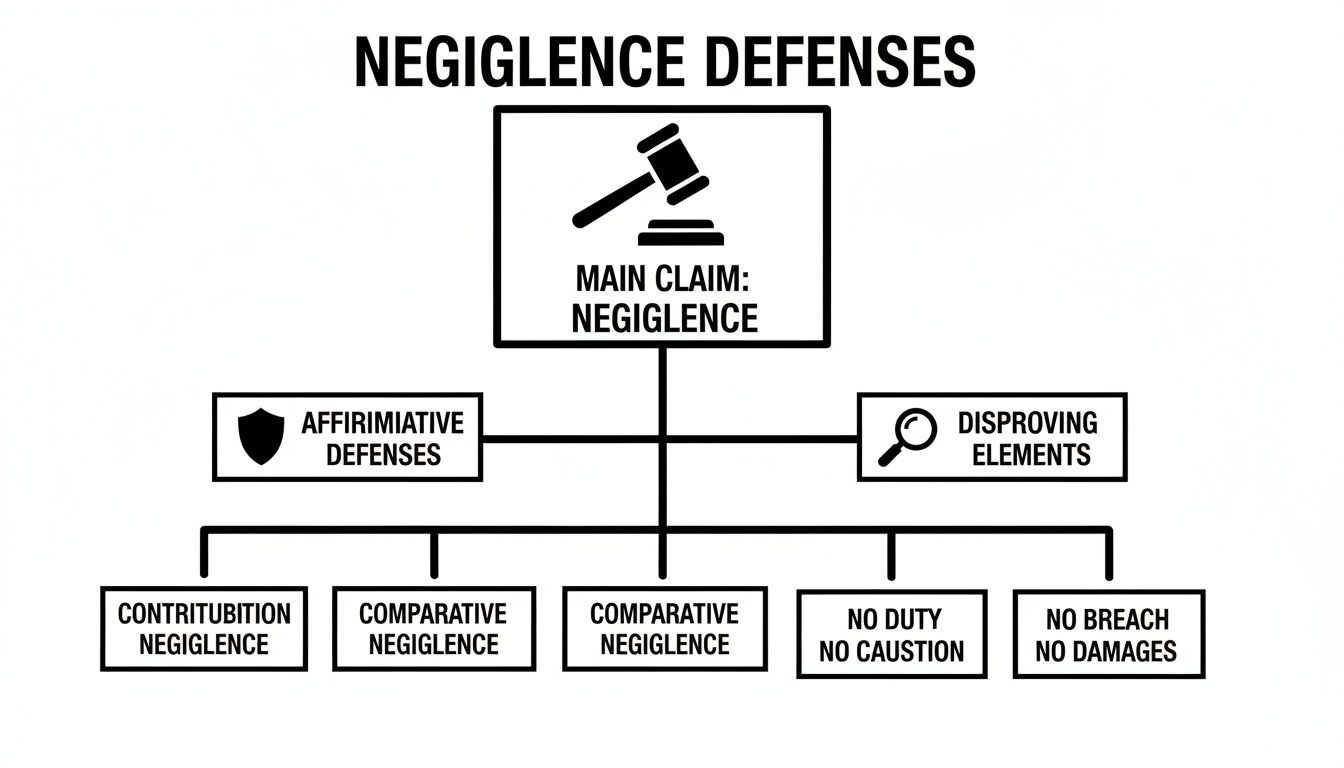

These defenses generally work in one of two ways:

- Affirmative Defenses: Here, the defendant essentially argues, "Even if I was negligent, there's another reason I shouldn't be held fully responsible." The most common example is pointing out that the injured person was also careless, contributing to their own harm.

- Disproving an Element: This strategy involves a more direct attack on the plaintiff's case. The defendant argues that the plaintiff failed to prove one of the essential building blocks of a negligence claim, like duty, breach, or causation.

This flowchart shows how these two paths diverge. A defendant can either introduce new information with an affirmative defense or dismantle the plaintiff's original argument piece by piece.

As you can see, a defendant has two distinct strategies to counter a negligence claim. They can either accept some of the plaintiff's story but add a new twist (an affirmative defense) or argue that the story itself is incomplete (disproving an element).

Defenses Play Out Differently Depending on the Case

The power of a particular defense often hinges on the specifics of the incident. In fact, real-world data from liability insurance claims shows just how much the success rate can vary.

For example, in medical malpractice cases, defendants have an impressive 81% success rate with their defenses. However, in standard motor vehicle accident claims, that number drops to just 39%. Cases involving dangerous properties (premises liability) or defective products fall somewhere in between, with success rates around 61-62%. You can dig deeper into these liability insurance statistics to see the full picture.

This data really drives home the point that the context of an accident is everything. The facts of the case dictate which defenses are viable and how likely they are to work, shaping the legal strategy from day one.

How Texas Applies the 51% Modified Comparative Fault Rule

In personal injury cases, assigning blame is rarely a black-and-white issue. Texas law gets this, which is why the state uses a system called modified comparative fault, often referred to as proportionate responsibility. This is hands down one of the most common and powerful defenses you'll see in a negligence lawsuit.

The best way to think about it is as a pie chart of responsibility. When a case goes to a jury, their job is to slice up that pie and assign a percentage of fault to everyone involved—that means the injured person (the plaintiff) and the person they're suing (the defendant).

Under this system, you can still get compensation even if you were partly to blame for what happened. But there's a huge catch.

The 51% Bar Rule Explained

Texas operates under what's specifically known as the “51% Bar Rule.” It’s a simple concept with massive financial implications for your case. Here’s how it breaks down:

- Your Damages Get Reduced: If a jury finds you partially at fault, your final compensation is reduced by your exact percentage of blame. So, if your damages are $100,000 but you’re found 20% responsible, your award is slashed by $20,000, and you walk away with $80,000.

- You Could Get Nothing at All: Here’s the "bar" part. If your share of the fault is determined to be 51% or more, you are completely barred from recovering a single penny. Your claim is worth zero.

This steep drop-off at the 51% mark makes it an incredibly potent tool for the defense. All an insurance company's lawyer has to do is convince a jury that you were just a little more than half to blame, and your entire case goes up in smoke.

The Takeaway: In a Texas negligence case, your ability to recover money depends entirely on being found 50% or less responsible. That single percentage point—from 50% to 51%—is the difference between getting a reduced payout and getting nothing at all.

A Practical Car Accident Scenario

Let’s put this into a real-world context. Picture a typical intersection crash. One driver is speeding, but they have a green light. As they enter the intersection, another driver tries to make a left turn, failing to yield the right-of-way and cutting right in front of the speeding car. A collision is unavoidable.

The case goes to trial, and the jury weighs all the evidence. They decide:

- The driver who failed to yield was 70% at fault.

- The driver who was speeding was 30% at fault.

Let's say the speeding driver's total damages are $50,000. Because they were found 30% at fault, their award is cut by that amount ($15,000). They will ultimately recover $35,000. Since their fault was well below the 51% bar, they were still able to get compensation.

For a deeper dive into this, you can learn more about how comparative negligence in Texas shapes case values.

When You Assume the Risk

Sometimes, you walk into a situation with your eyes wide open, fully aware of the potential dangers. In these cases, a defendant might argue that you assumed the risk, a powerful defense that can completely bar your negligence claim.

The core idea is simple: if you knew about a specific danger and voluntarily chose to face it anyway, you can't turn around and blame someone else when that exact danger leads to an injury.

This isn't just for extreme sports athletes. It comes up in more common scenarios than you might think. But for the defense to stick, the defendant has to prove two key things: that you actually understood the specific risk that hurt you, and that you willingly went ahead with the activity regardless. This defense generally falls into two buckets.

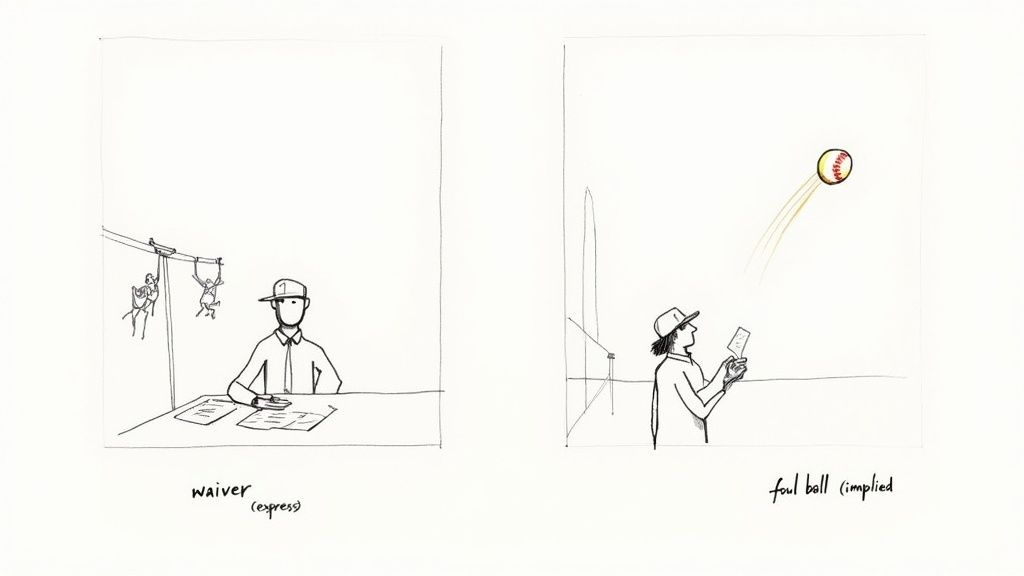

Express Assumption of Risk

This is the most clear-cut version of the defense. Express assumption of risk happens when you formally agree to accept the dangers, usually by signing something. Ever been to a trampoline park, gone horseback riding, or rented a jet ski? You almost certainly signed a liability waiver before you started.

That waiver is a binding contract. In it, you're explicitly agreeing that you understand the inherent risks of the activity and are giving up your right to sue if you get hurt because of those risks.

By putting your signature on that form, you’re providing the business with a powerful piece of evidence that says, "I get it, this could be risky, and I'm choosing to do it anyway." It creates a strong contractual barrier to a lawsuit if you’re injured by a danger that’s a natural part of the fun.

Implied Assumption of Risk

The other side of the coin is implied assumption of risk. This one is a bit trickier because it’s all about your actions, not your signature. The defense applies when a danger is so obvious and well-known that by simply choosing to participate, you are implicitly accepting the risks.

The classic example is going to a baseball game. Everyone knows a foul ball or even a broken bat could rocket into the stands. It’s a known part of the experience.

If you buy a ticket for a seat right behind the dugout with no protective netting, you’re implicitly agreeing to take on that specific risk. Getting hit by a foul ball in that situation makes a negligence claim incredibly difficult. The danger was open, obvious, and you chose to sit there.

But this defense isn't a get-out-of-jail-free card for defendants. It only covers the known, inherent risks of an activity. It generally won’t protect a defendant from gross negligence—that is, behavior showing a reckless indifference to safety. For example, if the stadium’s protective netting was old and full of holes, the assumption of risk defense wouldn't work. A faulty net isn't an inherent risk of baseball; it's just plain carelessness.

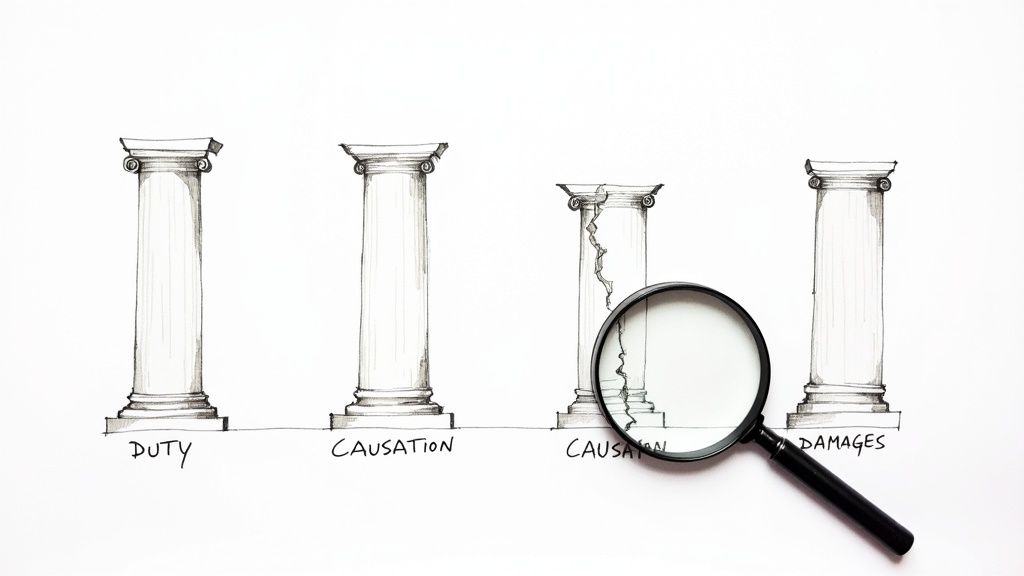

Disproving the Four Elements of a Negligence Claim

Instead of arguing about who was more at fault, sometimes the most powerful defense is to knock the legs out from under the plaintiff's case. Think of a negligence claim as a four-legged stool. For it to stand, the plaintiff must prove all four elements: duty, breach, causation, and damages. If you can prove just one of those legs is missing, the whole claim falls apart.

This isn't about shifting blame; it's about showing that the essential ingredients for a valid lawsuit were never there in the first place. Let's dig into how a defense can dismantle a claim, one element at a time.

Proving There Was No Legal Duty

The first question is always: did the defendant owe the injured person a legal duty of care? If the answer is no, the case stops right there. The level of duty you owe someone often hinges on the specific relationship between the parties, particularly in premises liability cases.

- To a Customer (Invitee): A business owner has a high duty of care. They have to actively look for and fix potential hazards, like a spill on the floor that could cause a fall.

- To a Trespasser: The duty owed to an adult trespasser is minimal. Generally, a property owner just has to refrain from intentionally harming them.

So, if a trespasser gets hurt by a rickety staircase the owner wasn't legally required to fix for them, the owner can argue that no legal duty was ever breached. That simple fact can end the entire lawsuit.

Showing There Was No Breach of Duty

Okay, so what if a duty did exist? The next move is to prove it wasn't breached. This means showing the defendant acted reasonably under the circumstances. It's not about being perfect, it's about being careful enough.

Take a classic slip-and-fall in a grocery store. The store's defense would focus on demonstrating that it met its standard of care. They can build this case with solid evidence, like:

- Cleaning logs showing regular safety sweeps.

- Security footage proving "wet floor" signs were put out immediately after a spill.

- Testimony from employees about their quick and proper response.

By proving they took all the reasonable steps to keep shoppers safe, the store argues it fulfilled its duty. This is also a cornerstone defense in medical malpractice claims, where the goal is to show a doctor's conduct met the accepted professional standard of care—a complex process that a recent 2025 medical professional liability update notes can take years to resolve.

Breaking the Chain of Causation

The third leg is causation. Here, the defense aims to prove that even if they were a little careless, their actions weren't the actual cause of the plaintiff’s injury. A great way to do this is to point to a superseding cause—a completely separate, unforeseeable event that swooped in and broke the chain of events.

Example: Imagine a driver causes a minor fender bender. No one is seriously hurt, and they pull over to exchange insurance info. Suddenly, a faulty construction crane on a nearby site collapses, dropping debris on one of the cars and severely injuring the driver.

The initial driver was negligent, sure, but they couldn't possibly have foreseen a crane falling out of the sky. The defense would argue the crane collapse was a superseding event and the true cause of the serious injuries, not the minor car accident.

Demonstrating a Lack of Damages

Finally, even if there was a duty that was breached, a negligence claim goes nowhere without provable damages. A plaintiff has to show they suffered some kind of actual harm, whether it's financial (like medical bills) or non-financial (like pain and suffering).

No harm, no foul.

For example, if a pharmacist accidentally fills a prescription with the wrong medication, but the patient notices the mistake before taking any pills, no injury occurred. The pharmacist was careless, but since there was no harm, there are no damages to sue for. The case is over before it begins. Proving or disproving these elements often comes down to compelling evidence, and you can learn more about the critical role of what is expert witness testimony in our detailed guide.

Procedural Defenses Like Statutes of Limitations

Not every defense in a negligence case is about dissecting the accident itself. In fact, some of the most powerful and final defenses have nothing to do with who was at fault. These are procedural defenses, and they're all about following the technical rules of the legal game.

Think of it like trying to score in basketball. It doesn’t matter how perfect your shot is if you don't get it off before the shot clock buzzes. Once that buzzer sounds, the play is dead. The legal system has its own shot clock, and it's called the statute of limitations.

In Texas, for almost all personal injury claims, you have two years from the date of the injury to file a lawsuit. This isn't a suggestion; it's a hard deadline. If you miss it by even a single day, the court will almost certainly throw your case out, no matter how clear the other party's fault was. This recent example of a court dismissing a motor vehicle accident claim due to the statute of limitations shows just how unforgiving this rule is in practice.

The Discovery Rule Exception

Now, the law does recognize that some injuries aren't immediately obvious. For these rare situations, Texas has a narrow exception known as the "discovery rule."

This rule says the two-year clock doesn't start ticking until the date you discovered your injury, or the date you reasonably should have discovered it and connected it to someone else’s actions. It’s a high bar to clear and only applies in very specific circumstances, like a surgical instrument being left inside a patient that isn't found for years.

Governmental Immunity: A Powerful Shield

Another major procedural hurdle is governmental immunity, sometimes called sovereign immunity. This is a very old legal principle that essentially shields government bodies from lawsuits unless they specifically agree to be sued. It covers everyone from federal agencies all the way down to your local city council.

The core idea is to protect public funds from being constantly depleted by litigation, but it can feel like an insurmountable wall for an injured person.

Suing the government isn't impossible, but it is exceptionally difficult. The Texas Tort Claims Act carves out limited exceptions where this immunity is waived, allowing citizens to file claims under specific circumstances.

One of the most common exceptions involves car accidents caused by a government employee on the job, driving a government vehicle. So, if you're hit by a city-owned truck or a public school bus, you might have a path forward. But even then, these claims are loaded with unique traps, like strict pre-suit notice deadlines and caps on the amount of damages you can recover.

These procedural defenses are incredibly effective. Data shows that while defenses in standard car accident cases succeed 39% of the time, they are successful in a staggering 81% of medical malpractice cases, where complex deadlines and rules often come into play. You can discover more insights about these personal injury law statistics on clio.com.

How These Defenses Shape Your Settlement Offer

Knowing the different defenses to negligence isn't just for lawyers. It's the key to understanding the one thing every client asks: "What's my case really worth?"

Insurance adjusters and defense lawyers are professional risk assessors. They spend their days calculating the odds of winning in court. The more confident they are in their defenses, the lower their settlement offer will be. It's that simple.

Think of it like a high-stakes poker game. A solid defense—like clear evidence you were partially at fault—is a trump card for their side. They'll play that card to push your case's value down, knowing that a jury might agree with them and slash your award or even give you nothing at all.

The Real-World Math Behind a Settlement

This isn't just a feeling or a negotiating tactic; it's cold, hard math. Insurance companies have a formal process for this. They start by estimating the full, best-case-scenario value of your damages—every medical bill, lost paycheck, and ounce of pain and suffering. Then, they start chipping away at that number based on how strong their defenses are.

Let’s walk through a quick example to see exactly how this plays out.

Scenario: Imagine an insurance adjuster agrees your total damages from a car wreck are worth $100,000. But, there's a catch. The police report notes you were looking at your phone right before the impact. The other side's attorney feels they have a strong shot at convincing a jury you were 40% to blame.

This is how that one defense completely changes the negotiation:

- Full Case Value: $100,000

- Your Potential Fault: 40%

- The "Defense Discount": $100,000 x 0.40 = $40,000

- New Settlement Target: $60,000

Thanks to Texas's comparative fault rule, the initial offer you see probably won't be anywhere near $100,000. It's far more likely to be in the ballpark of $60,000. The insurance company has already subtracted the amount they believe they can "blame" on you. This is precisely why these defenses matter so much—they are the levers the other side pulls to pay you less.

Frequently Asked Questions About Texas Negligence Defenses

When you're dealing with a personal injury claim, the legal jargon can get confusing fast. Let's cut through the noise and answer some of the most common questions people have about how these defenses work in the real world here in Texas.

If I'm Partially to Blame, Can I Still Get a Settlement?

Yes, absolutely—but there's a huge catch. Texas operates under a rule called modified comparative fault, sometimes known as the 51% bar rule.

What this means is you can still recover damages as long as a jury finds you are 50% or less responsible for the accident. Your final award is simply reduced by your percentage of fault. So, if you have $100,000 in damages but are found 20% at fault, you’d receive $80,000.

The critical part is the 51% threshold. If you are found to be 51% or more at fault, you get nothing. It's a harsh cutoff that makes proving the other party's overwhelming responsibility essential.

I Signed a Waiver—Does That Mean I Gave Up My Right to Sue?

Not necessarily. Signing a waiver, legally known as "express assumption of risk," creates a high hurdle for your case, but it doesn't automatically kill it. A waiver is not a get-out-of-jail-free card for a business's carelessness.

A Texas court might throw out a waiver if:

- The wording is confusing, ambiguous, or hidden in fine print.

- It tries to excuse gross negligence or intentional acts of harm.

- The injury was caused by a risk you couldn't have possibly anticipated.

Think of it this way: a waiver for a rock-climbing gym probably covers you if you slip and fall from a difficult hold—that's an inherent risk. But if your safety rope snaps because it was frayed and old, that's not a risk you agreed to. That's a case of the gym failing to maintain its equipment safely.

Key Takeaway: A waiver is designed to cover the known, obvious risks of an activity, not to give a business a free pass to be reckless.

What's the Difference Between My Fault (Comparative) and a Superseding Cause?

This is a great question because these two defenses get mixed up all the time, but they point the finger in completely different directions.

Comparative fault is all about your contribution to the incident. The defense attorney is trying to shift blame onto you to reduce or eliminate what their client has to pay.

A superseding cause, on the other hand, is about a completely separate and unforeseeable event that swoops in and becomes the real cause of your injury. It's an act of god or a third party's bizarre action that breaks the causal link back to the original defendant. The argument is that the defendant's initial mistake is no longer the legal cause of your final, more severe injury.

At Verdictly, we believe that transparent data leads to fairer outcomes. Our platform provides access to real Texas motor vehicle verdicts and settlements, empowering you to understand case values before you negotiate. Search our database to see what similar cases have achieved.

Related Posts

A Texas Guide to Loss of Consortium Claims

Understand what loss of consortium means in Texas. This guide explains who can file, the evidence required, and how these complex claims are valued.

Kinds of Negligence (kinds of negligence): How They Impact Your Injury Claim

Discover kinds of negligence in Texas personal injury cases and how they can impact your motor vehicle claim. Get clear guidance on your rights now.

Calculating pain and suffering car accident: A Practical Guide to Damages

Learn how calculating pain and suffering car accident damages works, with factors and tips to maximize your settlement.